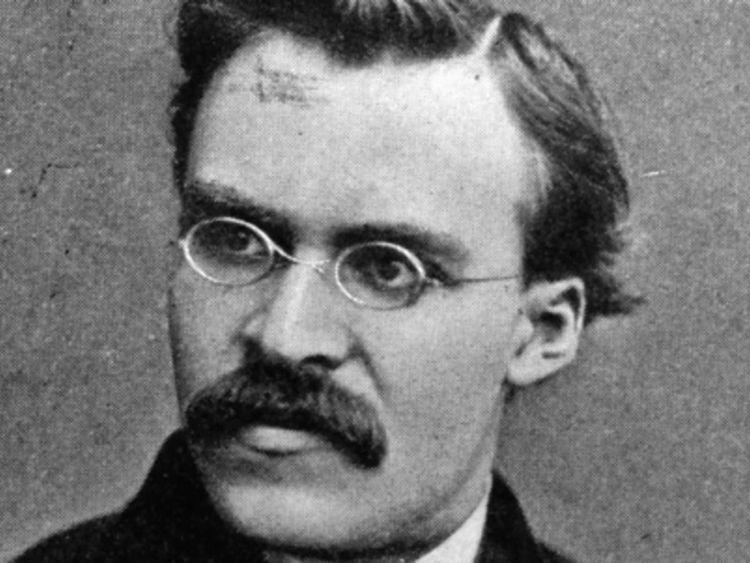

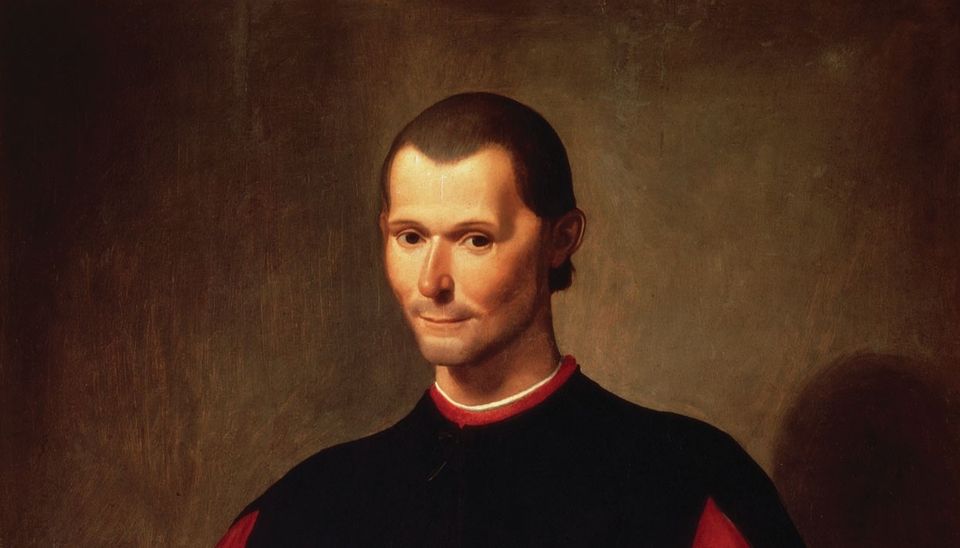

4 Takeaways from "The Prince"

Machiavellian—even today, nearly 500 years after Niccolò Machiavelli’s death, the term carries colossal weight and a rippingly negative connotation, bringing forth images of cruel, even sadistic, leadership. It may be the most widely known eponymous adjective in the West, bringing eternal infamy to the eponym himself. I recently finished Patrick Wyman’s fantastic podcast superseries on the early modern period, and I wanted to know just what made Machiavelli one of the most influential figures to come out of this period, so I read his famous treatise The Prince. In it, he explains how princes (his word for any monarchic ruler) in different situations should act—especially in the matters of public relations and war—and he supports his arguments with historical and contemporary examples. Instead of summarizing the book, I’m going to discuss four key takeaways I had, primarily about Machiavelli’s personal philosophy but also about the historical context of the book. The Prince is a quick read, and the ebook is practically free on Amazon, so if you wish to learn Machiavelli’s arguments in more detail, I recommend giving it a read.

1: Machiavelli Was Cold as Hell

Machiavelli positions himself as an objective observer—speaking bluntly and impassionately on everything from making war to feigning morality to appeasing citizens. He does so to create the mood of an instruction manual, while talking about cruelty and evil that nearly anyone else would discuss with strong emotion. Machiavelli was himself the Second Chancellor of the Republic of Florence until the republic fell to the Medicis in 1512, so he actively participated in the pan-European political world which he studied. His case for calculated authority without concern for morality is most explicit in Chapters 15 to 19, in which he discusses the character and reputation of princes. Machiavelli argues that—in order to succeed—princes must concern themselves with the appearance of morality but be ready to act immorally when it would benefit them. In today’s cynical age, this may seem only a simple observation, but in a time of divine kings who were expected to steer the morality of their subjects by example, this was a radical challenge to what made a prince fit to rule. To Machiavelli, morality did not justify authoritarian leadership but was instead an impediment to it.

2: Machiavelli Supports Tyranny

Before reading The Prince, I heard people claim that Machiavelli was merely an observer of the developing dynamics of power and did not express an opinion on the cold-hearted political tactics he outlines. This is not the case. As explained above, Machiavelli writes in a detached manner but not for the purpose of distancing himself from the tactics he outlines. His writing style only thinly veils his apparent implicit support for the immorality he preaches. If The Prince is a genuine manual for the powerful, then Machiavelli must not only believe in the efficacy of his suggestions but also be at peace with potentially causing the expansion of their use. The most powerful supporting evidence for the seriousness of The Prince—and, therefore, Machiavelli’s implicit amorality—is that it was written for presentation to Giuliano de'Medici, Florence’s conqueror prince who had recently exiled Machiavelli for his alleged support of a rebellious militia. For the rest of his life, Machiavelli attempted (semi-successfully) to regain the favor of the Medici family and work in their service. Given this aim, it seems reasonable that Machiavelli is indeed as sinister as he appears.

3: Maybe Not?

Machiavelli, though, is constraining himself to discussing authoritarian rule, while he himself worked for a republic and may have supported republican government. Indeed, The Prince allegedly influenced some future leaders who would help guide nations away from monarchies towards republics, but it is hard to determine Machiavelli’s intent. Without any context, it is easy to take the treatise at face value. However, Machiavelli’s absolute skewering of contemporary rulers seems almost comically unnecessary. To suggest that princes must be at times cruel, miserly, and areligious was one thing, but to support these claims with examples of contemporary rulers was blasphemous. Two of Machiavelli’s most prominent targets are King Ferdinand of Aragon and Pope Julius II. Machiavelli labels Ferdinand as miserly, and—in a thinly-veiled reference in chapter 18—attributes his success greatly to his deceit and trickery. Machiavelli even more aggressively assaults Julius II, who had recently passed. He highlights the late Pope’s supposed transition from generous cardinal to parsimonious Pope, characterizes him as an aggressive opportunist of the weakness of Italy, and repeatedly credits him with converting the Papal position into one with vast temporal (as opposed to strictly religious) power. In 1559, The Prince would ultimately be banned by the Church. This was supposedly due to its teachings of evil, but I find it hard to believe that the humiliating humanization of the Pope did not play a factor. As an experienced politician, Machiavelli surely knew the taboo of his aggressive, risky opposition to the image of the moral ruler, which brings into question whether his treatise was a genuine attempt at redemption. This—combined with Machivelli’s potential republicanism—has spawned a slew of alternative interpretations of The Prince as satire, subversion, or exposition rather than as a genuine manual for princes. Personally, I find the exposition angle compelling, especially considering that—according to Machiavelli’s own examples—contemporary princes didn’t need to be convinced to act immorally. If Machiavelli’s intent was to expose the inherent cruelty of absolute rule, then he may truly have been a republican citizen at heart.

4: Machiavelli Saw the Rising Tide of State-building

Machiavelli’s opinions aside, the most interesting historical takeaway from The Prince is the rising power of the state. While Machiavelli’s greatest personal influence for The Prince was his experience of the fall of the republic of Florence, his most-discussed influence was the Italian Wars more generally. In the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, semi-continuous conflict between nearly all of the European powers ravaged Italy for just over 65 years. Prior to these conflicts, Italy was the only major European region which was not gradually centralizing its power—remaining divided into city-states. Over the last few generations, the monarchs of Spain (Aragon and Castile), France, England, and the Holy Roman Empire used modern war finance, diplomacy, and growing social support for the right of kings to strengthen their power over their nobles and the Church. Concurrently, the Ottomans, an even more hyper-centralized power, were rising in the east. Italy became the ultimate European stage to flex this newfound state muscle, especially for Spain, France, and the Holy Roman Empire. Machiavelli recognizes this state-building (and Italy’s lack thereof) as the source of Italy’s recent woes, and he identifies unification as the only hope for the peninsula. If you take his authoritarian arguments at face value, he pleads for a new Cyrus, a truly great prince to return Italy to glory. If you believe him to be a man of the people instead, I still believe he genuinely wishes for unification, perhaps in the form of an Italian republic.

Regardless of Machiavelli’s actual personal beliefs and intent, The Prince is a critical historical and philosophical work, is the iconic text of political science, and is a fun quick read for fans of the early modern period.