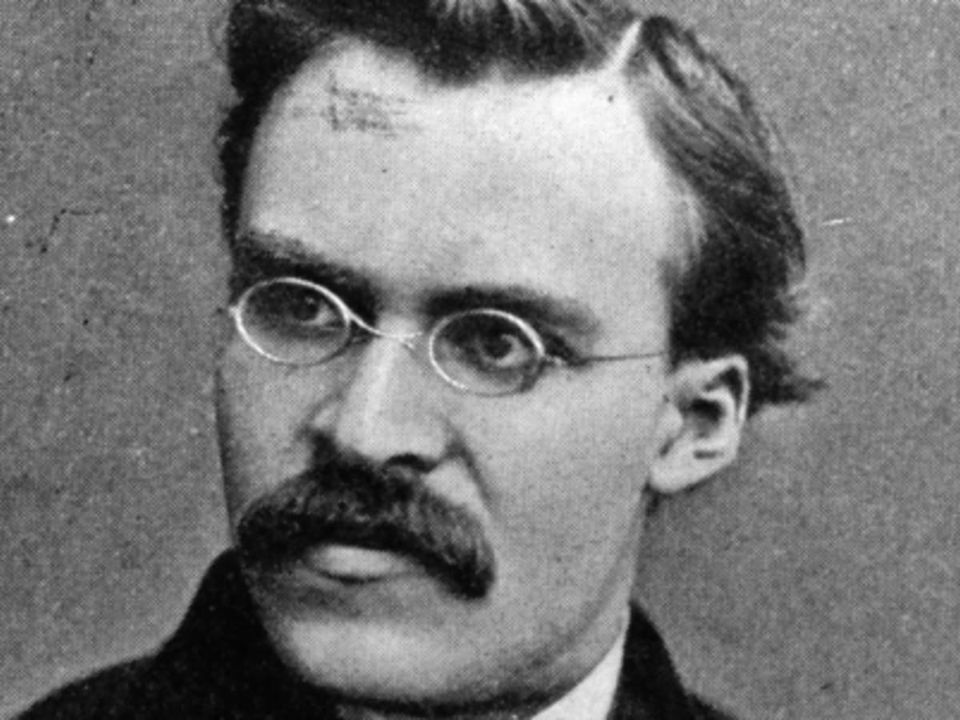

On "Beyond Good and Evil"

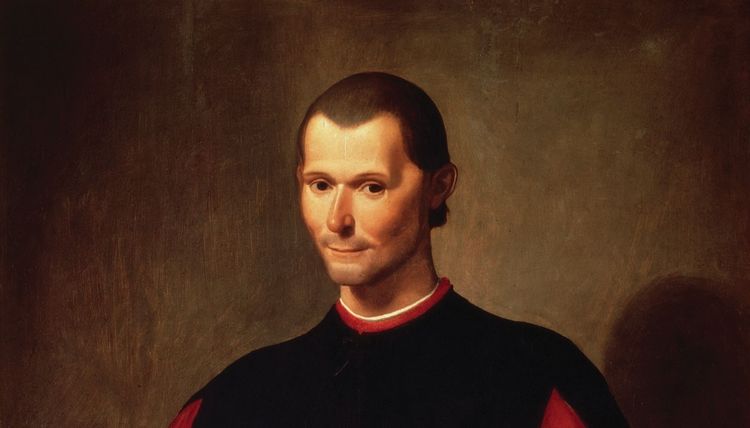

Do you recognize, accept, and appreciate your “will to power”? Well, Friedrich Nietzsche certainly hopes you will. Philosophy and deep thought is an interest of mine, and I have been listening to interpretations of philosophical and social theory on YouTube for a while now. I wanted to delve deeper—to read actual philosophical text and form my own interpretations. I’m not one for starting “at the beginning”; I’d rather jump in somewhere interesting and figure things out as I go along, so I started with Beyond Good and Evil. Yes, I knew that Nietzche is often tied to Nazism and—more recently—to general Internet edginess, but I also knew that he is one of the most influential philosophers on modern thought, especially posthumanist thought. So—relatively naive to Nietzsche’s actual positions aside from a vague notion of the terms “will to power” and “Ubermensch”—I dove in, and it was an exhilarating read! I’m going to present my thoughts on the book here with as little outside influence as possible. My interpretation may be amateur, but it is unquestionably mine.

Will to Power

Beyond Good and Evil is built on the foundation of the “will to power,” which Nietzche establishes as the driving force of all life. He does not seek to prove this to be the case, at least in this book, instead leaning on it as an assumption which he asks you to prove to yourself by examining yours and others’ actions. Reason has enabled humans to analyze and judge actions not just by their outcome but by their intent—their conscious driving force—which is the fundamental basis of most systems of morals. Nietzche describes the will to power as the subconscious driving force behind the conscious force of intent. The will to power is what drives us to succeed—to attain influence, fame, and fortune—not just on grand scales, but in our day-to-day lives. And the will to power isn’t altruistic: It is cunning, possessive, and forceful. It creates an itch which at its most irritating can only be scratched by domination, deception, and the search for power at all costs. This fundamental force is as crucial to Beyond Good and Evil as it is to life, and Neitzsche builds his core arguments on top of it.

Anti-humanism

Neitzsche is outright opposed to Humanism, a system of thought based on the fundamental belief in human exceptionalism. Humanism holds that because reason, self-awareness, and subjectivity are strictly human features, they set us apart from animals and should form the basis for all our actions. The ideal Humanist society is built on rational structures, teaches and requires moral behavior, and provides everyone with personal liberty. For Neitzche, the will to power makes this fundamentally impossible: Humans are not different from animals because all life is driven by this simple imperative. Reason, then, is not humanity’s key to conquering its animal instincts, but is instead humanity’s evolved method for enacting its animal desires more effectively. Morality itself then devolves into virtue signalling when examined on the subconscious level, revealing itself as just another way to attain and maintain status and power—our truly carnal needs.

Post-morality

The conclusion Neitzsche reaches is that morality is a tool humans use and change over time—not some higher truth after which philosophers should seek. Rather than continuing to analyze intention and morals, philosophers should look deeper; they should analyze the force driving and creating intention and morals—at the will to power.

More specifically, Neitzsche sees the current systems of morality, which preach human exceptionalism, personal liberty, and sympathy, as impediments to future human development. This “slave morality” (a concept established in more detail in his other works) acts to repress our will to power, invoking senses of guilt when we act upon it too severely. To advance humanity—according to Neitzsche—we should enable great men to be great by affirming and encouraging their will to power, not restricting it. Instead of concerning ourselves with the quality of life of everyone on Earth, Neitzsche pleads that we collectively accept and act upon our oppressive nature, eliminating the internal turmoil between oppressor and moralizer. The brutal, unapologetic conditions which inevitably would provide the challenges necessary to identify and elevate the truly great men to positions of dominance and control.

Bigotry

Significant portions of Beyond Good and Evil highlight Nietzsche’s misogynist and racist views. Most modern readings of Nietzsche aim to sift the gold out of the dirt and ignore these sections entirely. However, as a first-time reader, they caught my attention. In these passages, Nietzsche tries to justify the results of the will to power, explaining that there exist gradations of people who naturally will attain different levels of success in life. To me, this seems like a twisted sort of moralizing in a book so focused on moving beyond moral systems. Nietzsche seemingly felt a need to make the will to power appear ultimately just and fair according to these gradations. Now—nearly 150 years later—we know that these racist and misogynist generalizations are false, and yet, I still find Nietzsche’s will to power argument compelling and interesting. The fact is, the will to power is not fair; it is not just. Your place in society is not strictly representative of your intelligence, talent, skills, and will. Luck is massively important in life, perhaps more so than any other factor; however, even if successfully scratching the will to power’s itch is 99% luck and only 1% skill, then—over a sufficiently large amount of time—the effect of skill will be monumental on the direction humanity takes. The will to power oppresses, and—contrary to Nietzsche’s beliefs—those it oppresses do not deserve it, but it continues anyways, forcing us upwards and outwards, to goals unknown and potentially nonexistent. To believe that we—with our meager 10,000 year history—can accurately perceive and assess the results of the constant march of the will to power, is foolish.

My Thoughts

I find the foundation of Neitzsche’s position—that the will to power exists in all of us and runs counter to Humanist morality—compelling. I think we live in a cynical age which makes this easy to believe: Every day we are bombarded with the reality of people favoring their own benefit over morality. Politicians deceive and manipulate their voter bases, corporate executives treat their overseas workers as only a half-step above slaves, and many of us promote liberal values as if we do not benefit immensely from oppressive systems. Yes, these actions cannot fairly be judged in a vacuum because they exist within the intricately complex web of modern life, but they help to reveal the thinly-veiled immorality which dictates our lives. And to believe that those with the most power are some other breed of particularly evil humans foolishly ignores the rest of the world’s complicity. Being powerful simply provides people with the opportunity to act on the will to power even more; it does not create the will to power.

That being said, the prospect of a cultural and moral realignment to encourage the will to power scares me. Even if Humanist morality is just something instilled into me, learned rather than instinctive, it is still learned at the very core of my being, woven into my heart. I cannot easily let go of those beliefs, especially with the knowledge that their existence benefits me and everyone I know—those who would be trampled by the powerful otherwise. Perhaps this too is my will to power, my continued support of a morality which benefits me.

Conclusion

Even considering its unsavory chapters, I thoroughly enjoyed Beyond Good and Evil. The society and moral structure it challenges is perhaps even more powerful and all-encompassing today than it was in Nietzsche’s time. More than maybe any other set of beliefs, the morality of good and evil is ingrained in society to the point of appearing like fact. It is practically unimaginable that a radically different moral structure could prevail or frankly even exist. Nietzsche’s perspective that there are deeper truths than morality itself is fascinating and led me to deeper introspection about my own actions and intentions. I am not convinced that realigning our morality and cultural values to give free reign to the will to power will aid humanity’s development and evolution, but I am now more conscious, appreciative, and fearful of the ways the will to power tugs at the hearts and minds of every one of us.