Petit Bourgeois

Somewhere in our lives, we are each caught in the middle, torn between worlds, between lives and personalities, undecided and uncertain. We’ve all been a fence sitter once, or twice, or every day. We dance the ballet, perching on our toes, appeasing each voice of our internal dialogue and of each of our peers. We glide gracefully across the stage, until the sudden, harrowing realization that the slightest misstep, slip, or trip will bring it all crashing down, inviting the ire of the entire world, ourselves included. Decisions are hard. Shifty, weighty, complex decisions are harder. Knowing where you stand and committing to it, well I know at least I’m no good at that. And I know I’m not alone among the uncommitted ranks of the petit bourgeois. We walk a lifelong tightrope with a briefcase in one hand and a picket sign in the other. This impossible balancing act—this infinite noncommittal—makes us Capital’s secret weapon.

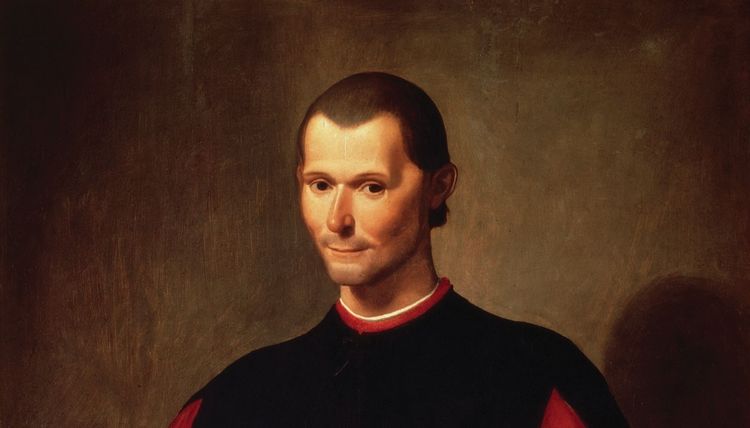

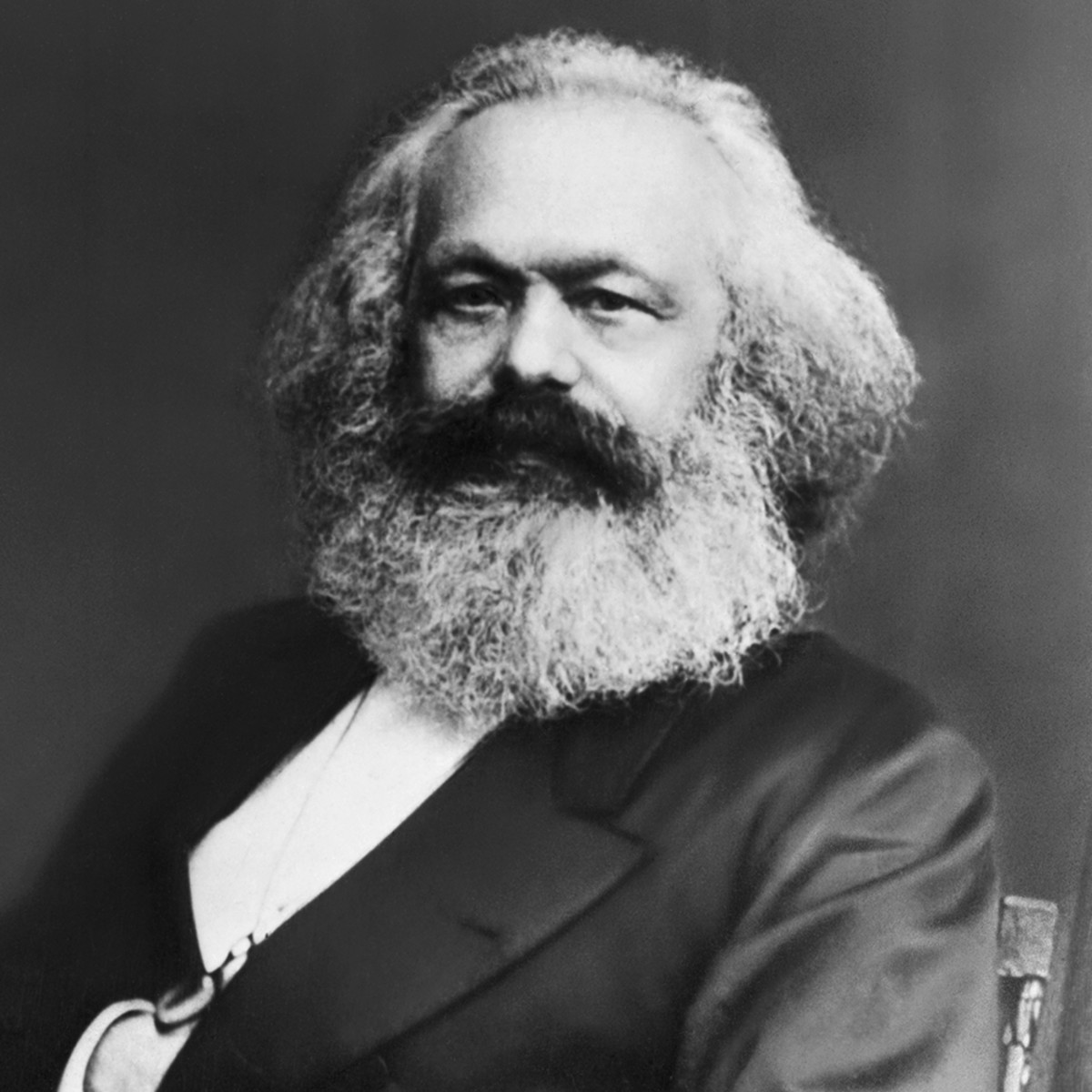

The petite (or petty) bourgeoisie is a term which hails from the ether of the late 18th or early 19th century, but it owes its first concrete definition to Karl Marx, who described it as the class where the interests of the proletariat and the bourgeoisie intersect and become blurred. He explains that the petit bourgeois have used the tools of capitalism to elevate themselves above the average worker but not to the point where they can confidently live off of ownership exclusively without fear of economic downturn. I love this definition, and while more modern class structure definitions with technical divisions between many smaller classes have their place, they lose the essence nailed by Marx’s simplicity: There are people who sell their labor and benefit little from economic growth, people who don’t sell their labor and benefit greatly from economic growth, and people who are somewhere in-between. Marx’s major error, however, was in assuming that the petite bourgeoisie's precarity would lead to its inevitable downfall. Perfectly efficient Capital, he believed, would perfectly stratify the population into owners and workers. Well, I can’t see the end of time, but it’s been 150 years, and we—the messy in-between—are still here.

It is true, though, that the modern petit bourgeois is not the same as that of Marx’s day. Innanja M. discusses this transition in their piece on the petite bourgeoisie. They highlight the cultural shifts which led to the rise of the yuppies and bobos of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, especially focusing on the vilification of the stereotypical mean, aggressively-capitalist small business owner as a driving force of this change. The petite bourgeoisie’s self-portrait has certainly changed in an attempt to combat that “mean, aggressively-capitalist” part, but the “small business owner” part has undergone its own transition as well. The American small business is far from dead, but it’s hardly thriving, either. The number of small businesses with employees has been stagnant for at least 30 years, and of course the past couple of years have been especially cruel to the small-time employer. The challenges of this group do not spell the end of the petite bourgeoisie, however. They are only one subgroup in a class now dominated by middle management and the stock-based compensation package.

Most of today’s petit bourgeois don’t own a shop or a restaurant on main street. They might hire and fire employees, but they aren’t their own boss either. They sell their intellectual labor as office (or home office) employees. So how exactly are they anything other than better-paid proletariats? Even a middle manager is just a salaryman—not materially incentivized by the growth of the economy—not an owner. The stock-based compensation package changed all of that. I couldn’t track down the concrete beginning of widespread stock compensation outside the c-suite, but the earliest reference I found to it was the Federal Accounting Standards Board’s guidance for stock compensation accounting in 1995. This leads me to believe (unsurprisingly) that stock compensation first grew to prominence in the early tech capital frenzies of the 80s and 90s. Now share-based compensation is a staple of the tech industry, especially in web companies. Most of today’s petit bourgeois aren’t small business owners, they are small owners of big businesses.

Now, if we were talking about a handful of shares to sweeten up an employment contract, I wouldn’t be writing this right now. Some have estimated that around 900 Google employees became instant millionaires when it IPO’d in 2004. Any of those employees who did not sell now holds at least $60 million of shares. Yes, Google is the absolute best case scenario, but the point remains: You can make real money from stock compensation packages. For tech employees, strong performance of their company and of the tech sector more broadly can and does lead to early retirements and sometimes even real riches. Ownership incentive of the petite bourgeoisie is alive and well, and the recent rise of crypto token-based compensation is greasing the gears for the next generation. When tech business does well, tech employees do well.

Of course, workers benefiting from the success of the company is a win-win. The laborer recoups some of the value of their labor, and the business receives an extra-motivated workforce in return. But nothing is ever that simple, is it? The worker, now aligned with Capital, finds the very precarity Marx identified 150 years ago. They could lose their job before their shares vest or gain enough value to be used as a primary income source, or their company could struggle, leaving them—unable to diversify their restricted shares—with scraps. The petit bourgeois can always become proletariat again. We live in purgatory, wondering if the groundhog will see his shadow, signaling another 30 years of labor.

This precarity creates the petit bourgeois’ dilemma: Which side am I on, anyways? Let’s be clear: new social programs, increased corporate taxes, and labor rights will harm our socio-economic standing and our chances at an early exit from the game. But if we side with Capital, and then those shares don’t work out as planned, then we’ve just been sharpening the blades on the wood chipper before jumping in. And we did not grow up around money: Our friends are proletariat; are we to forsake them and their struggles? I think we modern petit bourgeois recoil at these thoughts and try our best to compensate by being good little Democrats at the ballot box. We don’t want to side with the bourgeoisie, right? But, in private, we still celebrate when the company stock goes up. We still benefit when those social programs and taxes we supported ultimately fail. Oh I guess it’s just a silver lining, a consolation, when tech regulations and antitrust cases stall, and we only get to retire a lifetime early instead. What a pity, a crying shame.

Whatever front I put on, I cannot forget in the depths of my subconscious that I am incentivized by Capital. I support labor rights and the goal of reducing wealth inequality, but I cheer when my shares do well after a year of favorable conditions for big business. I sit on my fence, and I balance on my tightrope. I am Capital’s secret weapon: an educated, politically-informed laborer who gets a dopamine rush when stocks go up. I won’t cry too loud if wages continue to stagnate. I won’t fuss too much if corporate taxes keep trending down. I won’t pout too long when a judge dismisses another big tech antitrust case. My bourgeois incentives affect every belief I have and every action I take, just as they do for each and every one of my fellow petit bourgeois. We live in a constant state of self-conflict. Even the most resolute leftist among us must grapple with their alignment with Capital. Even the most devoutly capitalist among us can become proletariat again. So, where do you stand?